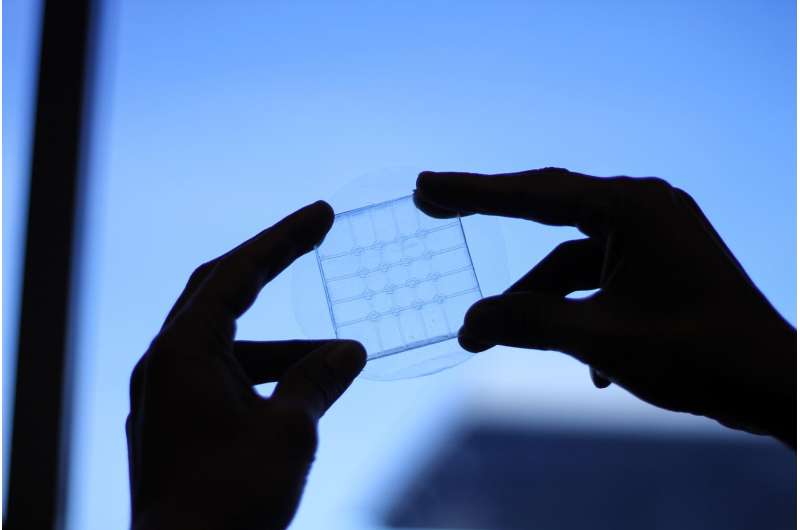

A closeup of the flexible sensor. Credit: University of British Columbia

Picture a tablet that you can fold into the size of a phone and put away in your pocket, or an artificial skin that can sense your body's movements and vital signs. A new, inexpensive sensor developed at the University of British Columbia could help make advanced devices like these a reality.

The sensor uses a highly conductive gel sandwiched between layers of silicone that can detect different types of touch, including swiping and tapping, even when it is stretched, folded or bent. This feature makes it suited for foldable devices of the future.

"There are sensors that can detect pressure, such as the iPhone's 3D Touch, and some that can detect a hovering finger, like Samsung's AirView. There are also sensors that are foldable, transparent and stretchable. Our contribution is a device that combines all those functions in one compact package," said researcher Mirza Saquib Sarwar, a PhD student in electrical and computer engineering at UBC.

The prototype, described in a recent paper in Science Advances, measures 5 cm x 5 cm but could be easily scaled up as it uses inexpensive, widely available materials, including the gel and silicone.

"It's entirely possible to make a room-sized version of this sensor for just dollars per square metre, and then put sensors on the wall, on the floor, or over the surface of the body—almost anything that requires a transparent, stretchable touch screen," said Sarwar. "And because it's cheap to manufacture, it could be embedded cost-effectively in disposable wearables like health monitors."

Sensors like the iPhone's 3-D Touch that can detect pressure, and some like Samsung's AirView that can detect a hovering finger. There are sensors that are foldable, transparent and stretchable. UBC researchers have developed a device that combines all those functions in one compact package -- the first stretchable touch sensor in Canada, and one that paves the way for foldable devices of the future. Credit: University of British Columbia

The sensor could also be integrated in robotic "skins" to make human-robot interactions safer, added John Madden, Sarwar's supervisor and a professor in UBC's faculty of applied science.

"Currently, machines are kept separate from humans in the workplace because of the possibility that they could injure humans. If a robot could detect our presence and be 'soft' enough that they don't damage us during an interaction, we can safely exchange tools with them, they can pick up objects without damaging them, and they can safely probe their environment," said Madden.

John Madden (left) and Mirza Saquib Sarwar have developed a stretchable touch sensor that could pave the way for foldable devices of the future. Credit: University of British Columbia

Coffee spill demonstration. Credit: Sarwar et al. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1602200

More information: "Bend, stretch, and touch: Locating a finger on an actively deformed transparent sensor array," Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1602200 , advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/3/e1602200

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by University of British Columbia