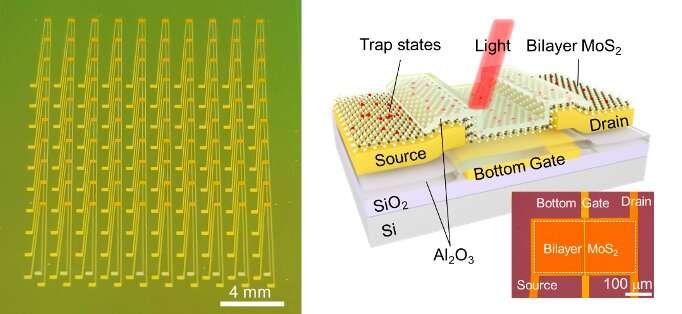

A photograph of the bio-inspired vision sensor array on a diced 2.5×3.0 cm2 chip (left), and schematic structure and optical microscope image of a single vision sensor (right). Credit: Liao et al.

To monitor and navigate real-world environments, machines and robots should be able to gather images and measurements under different background lighting conditions. In recent years, engineers worldwide have thus been trying to develop increasingly advanced sensors, which could be integrated within robots, surveillance systems, or other technologies that can benefit from sensing their surroundings.

Researchers at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Peking University, Yonsei University and Fudan University have recently created a new sensor that can collect data in various illumination conditions, employing a mechanism that artificially replicates the functioning of the retina in the human eye. This bio-inspired sensor, presented in a paper published in Nature Electronics, was fabricated using phototransistors made of molybdenum disulfide.

"Our research team started the research on optoelectronic memory five years ago," Yang Chai, one of the researchers who developed the sensor, told TechXplore. "This emerging device can output light-dependent and history-dependent signals, which enables image integration, weak signal accumulation, spectrum analysis and other complicated image processing functions, integrating the multifunction of sensing, data storage and data processing in a single device."

In 2018, Chai and his colleagues published their first paper on optoelectronic memories, where they introduced a resistive switching memory device, which could perform both photo-sensing and logic operations. One year later, the team presented a new optoelectronic resistive random-access memory device with three different capabilities. Specifically, this new device could sense the environment, store information in its memory, and perform neuromorphic visual pre-processing operations.

"In 2020, we examined the concept of near-sensor and in-sensor computing paradigms and provided our perspective in this field," Chai said. "Our new study builds on all of our previous efforts."

The intensity of natural light can vary significantly, with an overall range of 280 dB. When perceiving external light signals, the human retina adjusts the photosensitivity of its photoreceptors (i.e., rods and cones) according to the intensity of the signals. This ultimately allows the human eye to gradually adapt to different levels of illumination, to see well in both dark and bright environments, a capability known as "visual adaptation."

"For example, when you enter a darkened movie theater from a bright hall, you can hardly see anything initially, but after a while in the theater, it becomes easier to see," Chai explained. "This phenomenon is called scotopic adaptation. In contrast, if you come out of a dark movie theater on a sunny day, you feel very dazzled at first and it takes a while to see the surrounding scenery. This process is the opposite of scotopic adaptation, which is called photopic adaptation."

The key objective of the recent work by Chai and his colleagues was to build a sensing device inspired by structure and function of the human retina. To do this, they first started researching the retina and then tried to devise strategies that would allow them to artificially replicate its visual adaptation capabilities.

State-of-the-art image sensors based on silicon complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technologies typically have a limited dynamic range of 70 dB. This range is significantly narrower than the lighting range of natural scenes (280 dB).

"To enable vision under a large illumination intensity range, researchers have explored the use of controlled optical apertures, liquid lenses, adjustable exposure times and de-noising algorithms in post-processing," Chai said. "However, these approaches typically require complex hardware and software resources."

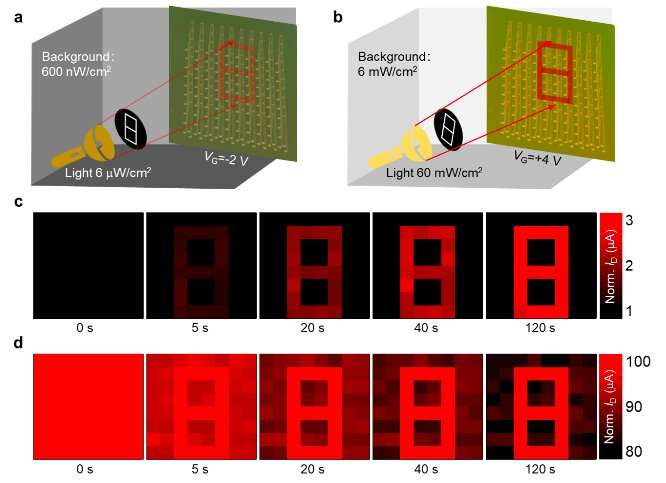

Scotopic and photopic adaptation of the bio-inspired vision sensor array. (a) Schematic illustration of an 8×8 pixel array under a dark background to recognize low-intensity image for scotopic adaptation test. (b) Schematic illustration of an 8×8 pixel array under a bright background to recognize strong light image for photopic adaptation test. The time-course of (c) scotopic and (d) photopic adaptation for the pattern of “8”. Credit: Liao et al.

Optoelectronic devices capable of visual adaptation and with a wide perception range at sensory terminals could have very valuable applications. For instance, they could help to improve the performance of computer vision tools, reduce the complexity of the hardware required to build robots or other sensing systems, and improve the accuracy of image recognition systems.

In the past, other research teams introduced optoelectronic devices that can adapt to different illumination conditions. Nonetheless, most previously proposed devices can only replicate the retina's photopic adaptation mechanism. The scotopic adaptation process, on the other hand, has so far proved to be harder to simulate.

"There is still a long way to go before we can fully replicate the retina's visual adaptation function," Chai explained. "To move towards this goal, we designed a phototransistor-type vision sensor using an ultrathin semiconductor, which can control the degree of scotopic adaptation and photopic adaptation in the same device by applying different gate voltages. In this way, we emulate the functions of photoreceptors and horizontal cells in the retina and successfully realized the bio-inspired in-sensor visual adaptation devices with an expanded perception range of 199 dB."

The bio-inspired vision sensor developed by Chai and his colleagues is based on a phototransistor made of an ultrathin semiconductor material (i.e., molybdenum disulfide). The phototransistors they used have several charge trap states, states that can trap or de-trap electrons within the channel under different gate voltages.

Ultimately, these states allow the researchers to dynamically modulate the conductance of their device. This in turn allows them to artificially replicate both the scotopic and photopic adaptation mechanisms of the human retina, enlarging the perception range of their sensor in response to different lighting conditions.

"Our sensor has several advantages and characteristics," Chai said. "Firstly, the visual adaptation function is realized in a single device, which substantially reduces its footprint. Second, it can achieve multiple functions with a single device, including light sensing, memory and processing. Finally, it can be used to perform scotopic and photopic adaptation to different background light intensities, simply by controlling its gate voltages."

Chai and his colleagues evaluated their bio-inspired sensor in a series of tests and found that it can effectively emulate the function of the human retina, achieving remarkable results in both scotopic and photopic adaptation. In addition, in contrast with previously proposed solutions, it has a significantly higher perception range (i.e., 199 dB).

"Our sensor can enrich machine vision functions, reduce hardware complexity and realize high image recognition efficiency," Chai said. "All of these benefits have great application prospects in the fields of automatic driving, face recognition and industrial manufacturing in complex lighting environments."

In their next studies, the researchers plan to improve the performance of their sensors further, while also using them to fabricate large-scale systems composed of an array of sensors. Ideally, they would like to build this sensor array on a flexible or hemispherical substrate, to achieve a wider field-of-view.

"An area for improvement is our sensor's adaptation time, as it is still not short enough to enable machine vision applications," Chai added. "Our target is to reduce the adaptation time to the microseconds level. The sensor array scale also needs further improvement. Our near-term goal of array scale is greater than 100×100. Finally, the heterogeneous integration of vision sensors and the post-processing units with Si-based control circuits is a very important step to move towards practical applications."

More information: Fuyou Liao et al, Bioinspired in-sensor visual adaptation for accurate perception, Nature Electronics (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41928-022-00713-1

Feichi Zhou et al, Low-Voltage, Optoelectronic CH3 NH3 PbI3− x Cl x Memory with Integrated Sensing and Logic Operations, Advanced Functional Materials (2018). DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201800080

Feichi Zhou et al, Optoelectronic resistive random access memory for neuromorphic vision sensors, Nature Nanotechnology (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41565-019-0501-3

Feichi Zhou et al, Near-sensor and in-sensor computing, Nature Electronics (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41928-020-00501-9

Yang Chai, In-sensor computing for machine vision, Nature (2020). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-020-00592-6

Journal information: Nature Nanotechnology , Nature Electronics , Advanced Functional Materials , Nature

Provided by Science X Network

© 2022 Science X Network