This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

reputable news agency

proofread

That blaring noise you heard? It was a test of the federal government's emergency alert system

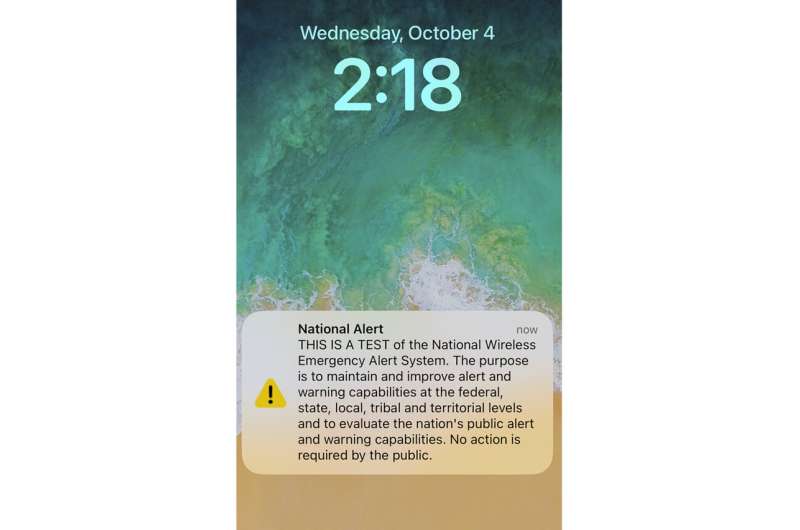

"THIS IS A TEST": If you have a cellphone or were watching television Wednesday, you should have seen that message flash across your screen as the federal government tested its emergency alert system used to tell people about emergencies.

The Integrated Public Alert and Warning System sends out messages via the Emergency Alert System and Wireless Emergency Alerts.

The Emergency Alert System is a national public warning system that's designed to allow the president to speak to the American people within 10 minutes during a national emergency via specific outlets such as radio and television. And Wireless Emergency Alerts are short messages—360 characters or less—that go to mobile phones to alert their owner to important information.

While these types of alerts are frequently used in targeted areas to alert people in the area to things like tornadoes, Wednesday's test was done across the country.

Antwane Johnson, the director of FEMA's Integrated Public Alert and Warning System which conducted the test, said afterward that he's confident the test performed as expected but that the government would gather and analyze data in the coming weeks to assess how it went. He estimated hundreds of millions of people received Wednesday's message.

Johnson said he'd already received reports from across the country of people who'd received the alerts including from colleagues at a conference for emergency managers in Tennessee. From where he observed the test, Johnson said he saw the entire map "light up."

"I am totally elated," he said.

The test was slated to start at at 2:20 p.m. Eastern time on Wednesday, although some phones started blaring just a few minutes before that. Wireless phone customers in the United States whose phones were on got a message saying: "THIS IS A TEST of the National Wireless Emergency Alert System. No action is needed." The incoming message also made a loud noise.

Customers whose phones were set to the Spanish language should have gotten the message in Spanish.

The test is conducted over a 30-minute window, although mobile phone owners should only get the message once. If their phones were turned off at 2:20 p.m. and then turned on in the next 30 minutes, they should have gotten the message when they turned their phones back on. If they turn their phones on after the 30 minutes have expired they should not get the message.

The message also went to people watching broadcast or cable television or listening to the radio. That messages said, "This is a nationwide test of the Emergency Alert System, issued by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, covering the United States from 14:20 to 14:50 hours ET. This is only a test. No action is required by the public."

Federal law requires the systems be tested at least once every three years. The last nationwide test was Aug. 11, 2021.

The test has spurred falsehoods on social media that it's part of a plot to send a signal to cellphones nationwide to activate nanoparticles such as graphene oxide that have been introduced into people's bodies. Experts and FEMA officials have dismissed those claims, but some social media users said they planned to shut off their cellphones Wednesday.

FEMA spokesman Jeremy Edwards said after the test was done that people have every right to turn their phones off to avoid the test but the organization hopes that after the test is done they make sure they turn their alerts back on because it's designed to make sure people can be reached in an emergency.

People on social media also suggested turning off phones for other reasons, such as not disturbing students and teachers in classrooms or children during naptimes at day care. At the White House, messages taped to chairs in the press briefing room asked members of the media to turn off their cellphones during the daily briefing.

Not everyone did.

Shortly before 2:20 p.m., journalists' and staff's phones began buzzing in the briefing room.

"Oh! There we go," said press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said. After joking that the briefing was over, she added, "It works. Every couple of years, folks."

Alarms continued to sporadically go off for a few minutes afterward.

The test also sparked discussion about how it could affect people in abusive situations. Some people in abusive situations have secret cellphones—usually with notifications muted—hidden from their abuser that allow them to keep contact with the outside world. Organizations that work with abuse survivors recommended they turn off their phones entirely during the 30-minute-long test Wednesday so as to not have the blaring noise give away to their abuser the fact that they have a secret phone.

© 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.