This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Q&A: A year after the fatal submersible implosion, just how safe are today's vessels?

Nearly a year after a submersible carrying five passengers imploded en route to the wreckage of the Titanic, another manned deep dive in the North Atlantic is reportedly in the works.

The billionaire-funded trip would take two men—Larry Connor, a real estate investor, and Patrick Lahey, co-founder of Triton Submarines—down some 12,500 feet in the summer of 2026 on a vessel that Triton is designing, according to the New York Times.

It would be the first manned mission to the wreckage since the OceanGate submersible tragedy on June 18, 2023, an incident that shook the industry and garnered international attention.

The pair say the acrylic-hubbed vessel would be the first of its kind to achieve such depths, and that they hope the trip will demonstrate that deep sea expeditions can be safely carried out.

But just how safe are today's vessels, and who signs off on them? Northeastern Global News asked Hanumant Singh, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern, who has overseen the design of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), to shed some light on the kind of tech needed to sustain a vessel at such depths.

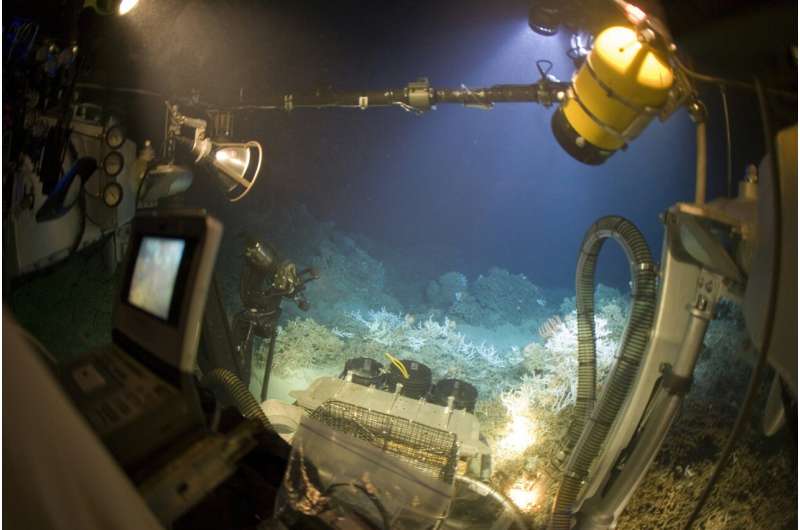

Singh has personally traveled down to similar depths on the DSV Alvin, a deep-sea research vessel that he says is "the most successful submersible" ever built.

Singh's comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Given the risks involved, why are people interested in these deep-sea missions?

There is something to be said about putting a person down so that they can have his first-person view. Having said that, you can pretty much do anything you want with robotic vehicles. They can go just as deep, and they're way safer.

Take the analog of space. The James Webb Telescope can give you so much information about the outer world. Meanwhile, we're actually going up into space, whether it's Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin vehicles, or other space shuttles—even though a lot of that work can be done remotely.

But there are reasons to put people up because, frankly, it's a better story to tell. There's a lot of fun in actually going out and doing it yourself.

How are these vessels certified, and who certifies them?

It's another interesting question to ask. How do you certify a manned submersible? We build so few of them. It's like, how do you certify a space shuttle? You've got all of NASA [National Aeronautics and Space Administration] working on that problem—and it's a big deal.

But when it comes to underwater vessels, the NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] doesn't do this. There's no one agency that certifies such vehicles. In fact, when you talk about certification for submersibles, usually it's something called the American Bureau of Shipping. They're used to certifying ships, but not manned submersibles.

The other option might be the Navy. But simply, we haven't built enough manned submersibles to know what's right and what's wrong, especially when we look at new materials. When you look at titanium, that's one issue; but when you look at these huge glass domes that these guys are talking about—that's a whole separate problem.

So how is it determined whether they are safe?

We know how aluminum and titanium—the two metals of choice—work underwater. The reason we like both is because they're the lightest metals, and they have good strength. We want them to be light, but they've still got to be heavier than water because we have to float them; we have to add something called syntactic foam so that, overall, the system is neutrally buoyant.

Think about what we do with our housing. We design our houses to 150% of pressure-rated depth, and then we test it to 125%, and we have a test protocol that we would use for certain systems.

But these are systems that we know very well. What we would do with a submersible is we would take it into a pressure chamber, cycle it to 125% some number of times, and then we would hold it at that depth for a period of time—four, six or 10 hours. Then we'd have a record that says this thing has been pressure-certified.

People build these chambers—there's one in Woods Hole; there are bigger ones elsewhere—and you put it inside and use hydraulic pressure to pump down to those pressure. (All of this is happening inside a concrete-reinforced building, because if something fails during a pressure test, it's a lot of energy that is released.) That's how we do pressure testing.

When you look at a big submersible—think, again, about the big glass dome of a submersible—there might be one place in the world where we can fit the whole thing in there and take it to pressure.

Are the design considerations different for manned vessels compared with unmanned?

Oh yes. If an AUV is designed and you lose it, you lose a million dollars, but nobody gets hurt. You can take a lot more risk in your design than you would if it were a manned submersible. If there is a person on board—I don't care what you're going to do, you better not hurt them. You're not allowed to do that; it's absolutely forbidden. So there's a huge incentive to make the unmanned vehicles—you can take risks with them; you can be a little more forward with your thinking.

What happened to the industry after last year's tragedy?

In short, nothing. That guy [Stockton Rush] was a renegade; he was not part of the standard industry, and wasn't going to change how things worked. We have vehicles that are built out of carbon fiber—underwater gliders, and so on. He was so far out in left field that it just didn't make sense.

For one, if you look at Alvin, it has a dedicated ship with it. You look at the Japanese Shinkai 6500; it has a dedicated ship that accompanies it. It's a huge and heavy vehicle; to get it out of the water, that lift has to be human-certified because you're picking up a vehicle with a human in it. Not only is there a vessel, but that very vehicle has to dictate the shape of the ship. What this guy did … was take some random ship, float it behind him and tow it out.

Well, that was probably contributing to the cycle time failure, because you're towing it up and down on the waves as opposed to keeping it stable. It's not just the submersible, it's the ship. It's the operations and maintenance; it's how often you're doing inspections; it's the crew. All of that is important in conducting safe dives.

This story is republished courtesy of Northeastern Global News news.northeastern.edu.